We live in an oddly divided world. Software appears to be sprinting toward the future: large language models write working code, design candidate drugs and proteins, summarize complex legal contracts, tutor students, generate music and art, and even reason through problems that stumped classical AI models for decades.

Yet, when we turn away from screens and back to the physical world, the contrast is striking. Outside of tightly-controlled warehouses, most robots still struggle with basic tasks, such as folding laundry, cleaning a messy room, picking up irregular objects, loading a dishwasher, cooking, or setting a table reliably. We don't see autonomous home assistant robots that adapt to clutter, machines that safely navigate unpredictable environments, or systems that manipulate objects with the flexibility of even a toddler. In factories and labs, robots remain expensive, brittle, heavily scripted, and narrowly specialized.

This is why some roboticists, like Rodney Brooks, are skeptical of “vision-only” approaches to dexterity: manipulation depends heavily on touch, force feedback, and proprioception signals that are either missing or extremely crude in most current systems. Even if you disagree with his conclusions about humanoids, the underlying point is broadly true: in the physical world, the hardest parts of the problem are often the parts you can’t observe cleanly.

This gap seems paradoxical. If AI is so smart, then why aren't we surrounded by intelligent machines? The answer has everything to do with noise and uncertainty in the physical world. Language models operate in a rich yet surprisingly stable world: text has a consistent structure, digital actions are reversible, and nothing randomly slips, shatters, burns, or rolls off the table. The physical world is the opposite. It is full of friction, occlusion, unexpected dynamics, and constant randomness.

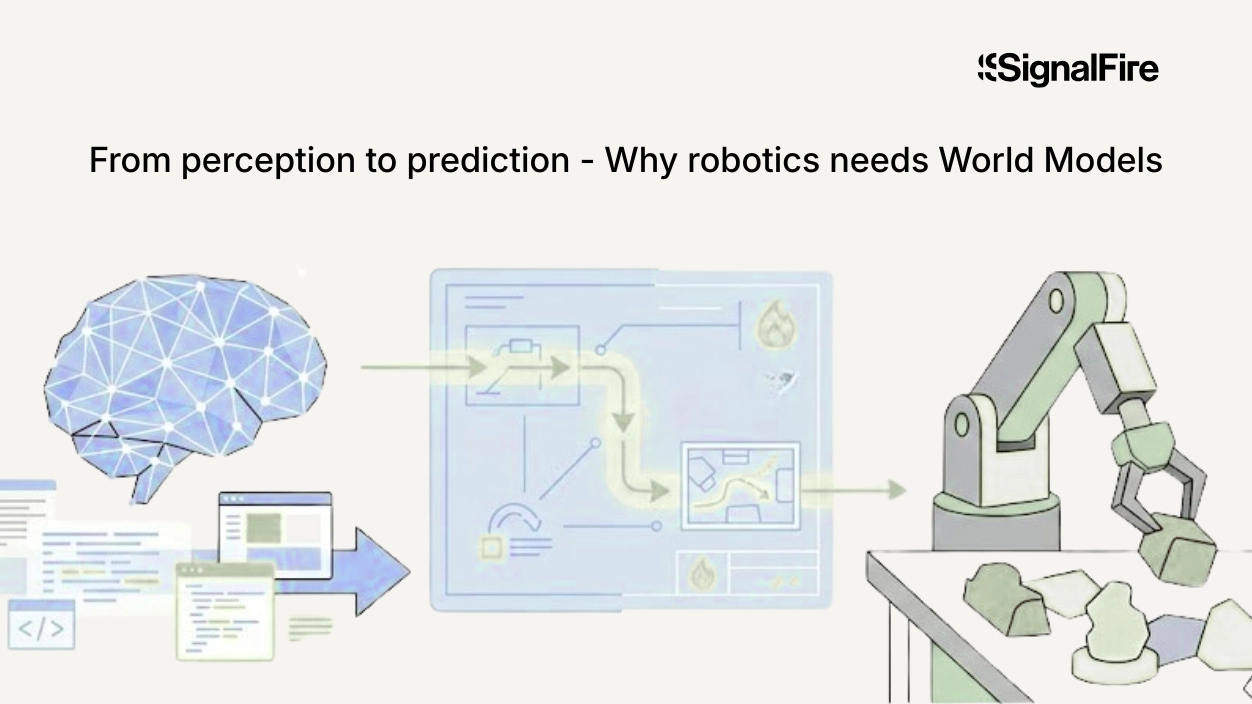

People often assume that researchers will eventually solve this robotics gap by somehow programming physics understanding into machines. However, when researchers discuss World Models, they aren't describing systems that model physics. These algorithms model reality by predicting it and learning directly from messy, unpredictable experiences. This shift is subtle but profound. If machines can learn the right abstractions from raw interaction with the world, robotics stops being an engineering project of endless edge cases and becomes a learning problem. What follows is a closer examination of how that representation works, why it has been so challenging to learn, and how new ideas are finally leading toward World Models that can effectively handle the real, noisy physical world.

The “World Model” problem

When we think of how humans make decisions and plans in the real world, we rely on an internal representation of our environment. When we “plan ahead,” we imagine the future states of the world that result from our actions. Crucially, this representation focuses only on the details relevant to the problem. For example, when someone maps their route to work, they consider streets, timing, and traffic, but their mental model doesn't include irrelevant details like the specific noises each car will make along the way.

At a higher level, we also organize our internal representations to reflect the structure of the world itself. This allows us to quickly adapt and fit new scenarios into familiar patterns. For example, when you encounter a door with a handle you've never seen before, you don't need instructions. You recognize it as a handle due to its shape and placement, which are similar in structure to your concept of a handle, and you already have a general understanding that “doors open by applying force to a handle.” Even without knowing the exact mechanism, you can infer that turning the handle should result in an open door.

It’s worth separating this from a more traditional robotics idea: a policy that maps observations directly to actions (“see this, do that”). A world model is not, by itself, a decision-maker. Its job is to predict how the world would change under different possible actions by producing a compact representation of future states rather than an immediate motor command. Once you have that predictive model, a planner (or downstream policy) can evaluate those imagined futures and choose the action sequence that leads to the best outcome.

Under this framework, a useful World Model must possess four properties:

- It must reflect how the world is structured, not just raw sensory data.

- It must generalize across multiple tasks, allowing adaptation without starting from scratch.

- It must filter out irrelevant details, focusing only on information that affects the outcome.

- It must predict how the world will change under different actions, enabling planning before execution.

Herein lies the challenge that today's frontier research faces.

Learning meaningful representations of the world

Historically, deep learning breakthroughs in perception accidentally produced structured representations of the world. In computer vision, models trained to classify images into cats, dogs, or elephants produced well-organized, surprisingly useful internal representations. In cases like this, where we optimize for a simple objective like predicting the contents of an image, the features learned along the way encode rich information about shape, texture, pose, and semantics. These representations can then be reused as state inputs for tasks like object detection, tracking, or segmentation, even though they weren't explicitly trained for those purposes.

We transitioned from classification-style approaches to training models on tasks such as image reconstruction, where the goal was to complete missing parts of an image given the remaining context. Overall, these approaches produced richer and more generalizable representations. But they still carried fundamental limitations. Sensory inputs often contain details that are unpredictable and irrelevant to any downstream task. For example, the precise ripples on the surface of a boiling pot are inherently random and irrelevant to downstream tasks. Yet reconstruction-based models must treat such details as information worth predicting. They try to encode and recreate randomness that has no value to World Models. In doing so, the resulting world representation becomes entangled with noise, rather than focusing on the meaningful structure of the scene.

Just as image reconstruction is a pattern-completion problem (given part of an image, predict the missing pixels), World Models can be viewed as a pattern-completion problem in time (given the current state of the world and a sequence of actions, predict the future state). Instead of filling in missing parts of an image, a World Model fills in the missing parts of the future.

This is where recent approaches like JEPA come into play. Rather than performing image reconstruction or predicting future video frames pixel-by-pixel, JEPA models focus on predicting abstract representations of the future conditioned on latent variables. Think of these latent variables as actions performed by a robot or other independent factors of change that could affect the future. In other words, they aim to model how the world changes without wasting capacity on irrelevant visual details. By learning to forecast the abstract state of a scene rather than its exact pixel-level appearance, these models begin to produce organized, actionable representations while filtering out the noisy details that pose such a problem for current robotics.

Through this approach, JEPA builds representations that are inherently predictable by capturing what is stable and meaningful about the world while discarding highly random details. The learning objective discourages encoding the exact pattern of steam rising from a kettle or the precise texture of a crumpled cloth, since such details are fundamentally unpredictable and make future predictions of the world state harder. Instead, to achieve strong performance, the models must represent the predictable aspects of those scenes that matter for understanding how the world will evolve. This architectural choice turns out to be crucial because the model's objective shifts from reconstruction to learning the world's predictable dynamics.

The noise and unpredictability problem

JEPA hasn't taken off in recent years because JEPA models struggle to distinguish noisy, unpredictable details from meaningful structure. Without the right constraints, these models tend to collapse into trivial representations. Imagine a filing system that solves the problem of too much information by throwing away entire categories of documents. In this way, JEPA models take shortcuts that ignore unpredictable noise, but in the process they also discard useful structure.

However, recent research has begun to develop theoretical tools to overcome this challenge. LeJEPA, introduced by Randall Balestriero and Yann LeCun, proposes a mathematically grounded regularizer that helps prevent this collapse. The core idea is to penalize degenerate world representations by ensuring that the space of internal representations maintains consistent resolution in all directions, rather than over-focusing variance on a small subset of features while ignoring others. Technically, this is achieved by shaping the embedding distribution toward an isotropic Gaussian. This constraint encourages the model to evenly utilize its representational capacity across dimensions, preserving a rich, well-conditioned internal representation.

This seemingly simple geometric constraint turns out to be powerful: It stabilizes training, preserves relevant structure, and enables JEPAs to learn rich, predictable representations without relying on heuristics such as data augmentations or contrastive negatives. Together, these advances mark a shift from ad-hoc techniques for preventing model collapse toward theoretically grounded approaches that promote learning the structure of the world directly, without being overwhelmed by noise.

World Models offer a new path

Taken together, these ideas suggest a fundamental shift in how we approach robotics. For decades, the field has been trapped in a cycle: hand-engineer solutions for specific tasks, watch them fail on edge cases, then add more rules and exceptions. World Models offer a way out. Instead of programming physics into machines, we can build systems that learn to predict and reason about future world states.

The path forward still has many unanswered questions:

- How do we efficiently guide these models to explore useful behaviors?

- How do we scale them to the full complexity of unstructured environments?

- How do we ensure they remain safe and aligned with human intent as they gain more autonomy?

These aren't trivial problems, but they're fundamentally different from the problems that have stalled robotics for the past 50 years. What's changed is that we finally have a theoretical framework that matches the problem structure.

LeJEPA and related approaches aren't just incremental improvements; they represent a mathematical foundation for learning World Models that can handle real-world uncertainty. For the first time, the gap between digital intelligence and physical competence looks less like science fiction and more like a research challenge we can overcome.

*Portfolio company founders listed above have not received any compensation for this feedback and may or may not have invested in a SignalFire fund. These founders may or may not serve as Affiliate Advisors, Retained Advisors, or consultants to provide their expertise on a formal or ad hoc basis. They are not employed by SignalFire and do not provide investment advisory services to clients on behalf of SignalFire. Please refer to our disclosures page for additional disclosures.

Related posts

The built economy: How vertical AI is unlocking the biggest untapped market in trades and construction

Why expert data is becoming the new fuel for AI models

LLM hallucinations aren’t bugs: The real challenges are confidence and context

Why expert data is becoming the new fuel for AI models